Sitting With the Ache: Why Demon Copperhead Refuses to Let You Look Away

- Danielle Robinson

- Dec 28, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 29, 2025

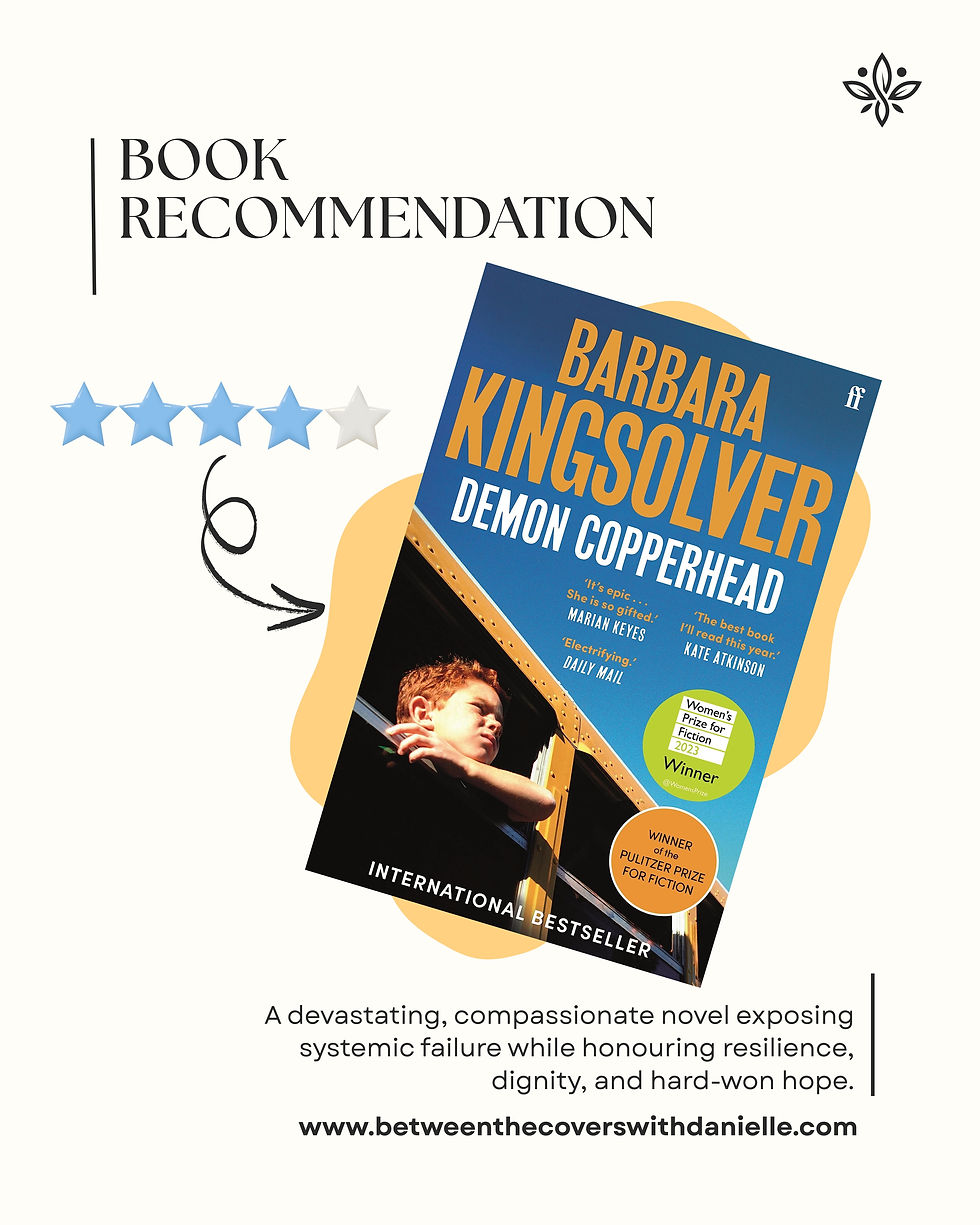

There are books you finish and immediately want to recommend, and then there are books you finish and don’t quite know how to speak about yet—because they’ve settled somewhere deeper than opinion. Demon Copperhead belongs firmly to the second category.

This is not a novel you “consume.” It’s one you carry.

Barbara Kingsolver has written an expansive, modern American epic that is at once intimate and systemic, fiercely compassionate and quietly enraged. It is a story about a boy growing up in rural Appalachia, but it is also a story about what happens when institutions fail, when poverty is inherited rather than chosen, and when survival itself becomes a full-time occupation.

Told in the first person, through the voice of Demon—a sharp, funny, deeply observant narrator—the novel refuses sentimentality while still offering tenderness. Demon is not a symbol. He is not a lesson. He is a person. And that distinction matters more than it might initially appear.

A Voice That Carries the Weight of a Life

What struck me first, and stayed with me longest, is Demon’s voice. Kingsolver understands something crucial: if you want a reader to sit inside injustice, you don’t do it through abstraction. You do it through language that feels lived-in.

Demon narrates with humour, defiance, and a self-awareness that borders on self-protection. He notices everything—the moods of adults, the social hierarchies at school, the way kindness often arrives inconsistently and disappears without warning. He jokes because joking is safer than pleading. He performs because invisibility is dangerous.

This voice does more than carry the story; it resists erasure. Demon tells his own life because too many systems have already tried to summarise it for him.

Childhood Without a Safety Net

Demon’s early life is defined by instability. Born to a teenage mother already worn thin by circumstance, he grows up in an environment where love exists, but reliability does not. The adults in his world drift in and out—sometimes through addiction, sometimes through violence, sometimes through sheer exhaustion.

One of the novel’s most devastating achievements is its refusal to romanticise hardship. Childhood here is not innocent. It is vigilant. Demon learns early how to read rooms, anticipate danger, and adapt to changing rules. The cost of that adaptation is profound, and the book never lets us forget it.

When Demon enters the foster care system, Kingsolver exposes something deeply uncomfortable: how easily care becomes commerce. Some of Demon’s placements are not merely neglectful; they are extractive. He is fed poorly, worked hard, and treated less like a child than a resource.

This is not written for shock value. It’s written with a matter-of-fact cruelty that mirrors how such systems often operate—quietly, bureaucratically, and without outrage.

The Illusion of Rescue

One of the most compelling tensions in the novel is its repeated flirtation with “rescue.” Time and again, Demon is offered what looks like stability: a roof, a routine, a chance to belong. And time and again, that stability comes with unspoken expectations.

When Demon is taken in by a respected high school football coach, the story briefly shifts tone. Life improves. He is safe. He is encouraged. He is fed. And yet, even here, Demon senses the fine print. His value is conditional. His body is useful. His pain, eventually, becomes manageable—pharmacologically.

This is where Demon Copperhead becomes devastatingly precise about the opioid crisis. Kingsolver does not frame addiction as moral failure. She frames it as chemistry meeting despair in a culture that monetises relief and then punishes dependency.

A sports injury leads to a prescription. The prescription leads to numbness. The numbness feels like mercy. And by the time the danger becomes visible, the damage is already embedded.

Love, Loss, and the Lie That Love Is Enough

Demon’s relationship with Dori is one of the novel’s emotional cores. Their connection is real, tender, and doomed—not because they don’t care enough, but because care alone cannot undo structural harm.

Their love unfolds alongside addiction, grief, and exhaustion. Intimacy becomes braided with escape. Responsibility arrives before either of them is equipped to carry it. When tragedy strikes, Kingsolver refuses melodrama. Loss here is blunt, private, and irrevocable.

What makes this section so powerful is its honesty. There is no moment where love “saves” them. There is no narrative shortcut where intention outweighs circumstance. The novel insists on a truth we often resist: affection does not equal capacity.

Consequences That Cannot Be Undone

As the novel moves into its final movement, consequences arrive not with theatrical flair, but with the cold logic of accumulation. Addiction narrows the world. Impulse overtakes foresight. And when catastrophe strikes, it takes more than one life with it.

The state reappears—not as care, but as punishment. Rehabilitation is enforced rather than offered. Accountability is unevenly distributed. Survival feels arbitrary.

And yet, Kingsolver does something extraordinary: she allows time to matter.

Recovery, when it comes, is not a montage. It is slow. Unremarkable. Often boring. Demon gets sober not because he is suddenly redeemed, but because he is finally given space, structure, and support long enough for choice to become possible.

This, to me, is one of the novel’s quiet triumphs. It honours the unglamorous reality of rebuilding a life.

Art as Autonomy

Throughout the novel, Demon draws. Art is his private refuge long before it becomes his public future. And when his talent eventually offers him a path forward, it doesn’t feel like a convenient twist—it feels earned.

What matters is not that Demon is “gifted,” but that someone finally treats that gift as legitimate. Not inspirational. Not decorative. Legitimate.

The novel understands that dignity often begins when someone takes your work seriously.

What This Book Asks of Us

Demon Copperhead is not interested in making readers feel virtuous. It is interested in making us attentive.

It asks us to look closely at how we talk about resilience, how easily we praise endurance while ignoring the conditions that demand it. It asks why we accept suffering as inevitable in certain communities, and why we are surprised when people seek relief wherever they can find it.

Most of all, it insists that people like Demon are not anomalies. They are outcomes.

When the novel closes with Demon finally reaching the ocean he once only imagined, the moment is not triumphant—it is quietly radical. Possibility, here, is not a promise. It is a horizon.

And perhaps that is the book’s greatest gift: not hope as fantasy, but hope as something earned slowly, imperfectly, and in full awareness of what it costs.

This is a novel that doesn’t just tell a story. It leaves a mark. And long after you’ve closed the book, you may find yourself asking harder questions—not about the characters, but about the world that shaped them.

That, to me, is what great literature does.

Much love,

Comments